Underworld Beauty Blu-ray Review: Noir subversion in post-war Tokyo

Seijun Suzuki's 1958 yakuza film is a radical departure from genre conventions.

This is Re/Play, a retrospective feature that examines whether classics, cult favorites, and other pop artifacts can withstand remastered scrutiny.

THE MOVIE: Underworld Beauty

ORIGINAL RELEASE DATE: March 25, 1958.

NEW FORMAT: New 4K restoration of the original print by the Nikkatsu studio with uncompressed mono PCM audio and improved English subtitles. From Radiance Films.

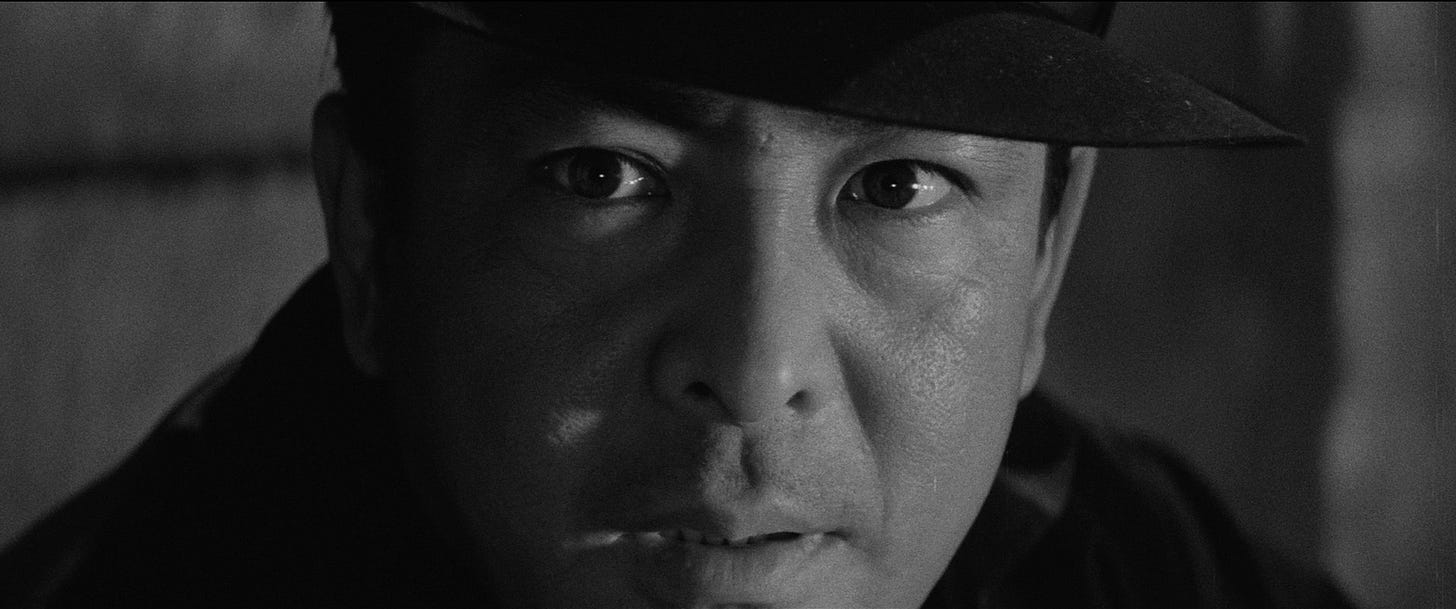

In keeping with the great noirs that pull us by the lapels into some fearsome criminal world, the first image we encounter in Underworld Beauty tosses us right onto the tracks. A man walks a lonely industrial street at night. Seijun Suzuki, utilizing Cinemascope for the first time in his rocky career with the Japanese film studio Nikkatsu, makes a feast of this opening shot: billowing smoke, hard edges, and long shadows. The man pries open a manhole with a crowbar and slips into the darkness below. A driver spots him and, startled, informs his oblivious companion, who cooly retorts, "It's a sewer. There's no way anything's moving down there."

If only they knew. Below, the man stalks through stagnant water, surreal ripples of light dancing off the wet brick. The score, by Suzuki's frequent collaborator Naozumi Yamamoto, veers into haunted house territory, working the theremin like a ghost is seconds away from floating into the frame. He hammers at the walls and uncovers a hidden cache. His treasure: a gun and two diamonds. From here, Suzuki hard-cuts to a bustling nightclub, a place of dancing, drinking, and fleeting pleasures, that Scope cinematography alive with frivolity interspersed with grim faces in big overcoats.

In Suzuki's Tokyo of 1958, nightlife pulses with heedless, post-war abandon, the tab paid for by graft and other criminal deeds. It explains the granite frown on the fellow we've been following; he's a hard man out to settle unfinished business in a world that has spun on without him.

His name is Miyamoto (Michitarō Mizushima), fresh from a three-year stretch for purloining those diamonds. His goal, we discover, is to fence them through his yakuza boss, Oyane (Shinsuke Ashida), as his thank you for not spilling about their organization while in prison. Miyamoto wants to give the proceeds to his former partner, who lost a leg during their ill-fated heist, a big ask for this has-been gunsel; naturally, Oyane has other plans. The elusive treasure driving the plot is a standard trope, and yes, the diamonds create a gravity well that yanks in every character in the film. That would be enough juice to fuel any other revenge thriller, but intriguingly, Suzuki's story interests lie elsewhere.

Underworld Beauty is about settling accounts, but it also radically challenges gender conventions in an era where Japanese women were often confined to demure, submissive roles. Suzuki's film introduces Aikiko (Mari Shiraki), the daughter of Miyamoto's partner, who becomes the former gangster's primary concern after his bungled diamond sale results in her father's demise. Aikiko defies easy categorization: she isn't a damsel but an energetic, Ann-Margret-like force, mercurial, strong-willed, and, when things inevitably go sideways in Miyamoto's plans, someone who plays an active role in the reckoning to come — her fate, in effect, entwined with the film's archetypal hero.

I don't dare spoil the wild twist during Miyamoto's diamond sale, but just wait until you see where those diamonds end up. From there, Aikiko's sculptor boyfriend, Arita (Hiroshi Kondō), blunders into Miyamoto's affair and puts Aikiko's life in the yakuza's crosshairs. Underworld Beauty gets to work subverting genre convention; in another version of this story, Aikiko would be an innocent fawn for Miyamoto to rescue and later woo. Not here. Suzuki, perhaps by studio edict, insinuates romance between these two characters (stark age difference notwithstanding), but his finale, which sees Aikiko standing with her back to our convalescing hero in a hospital, looking out toward a bright future (interestingly, with two birds in a cage deliberately placed next to her), suggests otherwise. Underworld Beauty gets its conventional happy ending but ends with a question mark instead of a period.

If Suzuki had taken a more traditional approach, it would be a given that hard-boiled Miyamoto gets the girl at the end or that tragedy strikes before romance could bloom. Suzuki doesn't play by those rules. Instead, he frees Aikiko to get her hands dirty in the film's action climax, set at an industrial coal deposit where Miyamoto digs a path away from their yakuza pursuers. Earlier, Shiraki is frequently shot in the buff or other forms of undress, yet Suzuki doesn't sexualize her physicality. He knows Shiraki is just as much an indomitable presence as Mizushima; they both peel off their shirts, pick up shovels, and together let their muscles do the talking, gender convention be damned.

Symbolism plays a big role. The contrast of coal and diamonds, two lovebirds in a cage and the open air beyond it, Underworld Beauty dutifully supplies imagery that both compliments the typical gangster yarn and challenges it. Another shot puts things in an odd light. Miyamoto later returns to that sewer where the film began and makes a troubling, if revealing, discovery: a broken mannequin floating in sewage. In a moment of reflection, Miyamoto sees something in the desolation of the thing — something broken but beautiful and worthy of a second life, which we're meant to see as Aikiko. This lends a paternal undertone to their relationship, gently softening Suzuki's earlier subversions. Aikiko is a free spirit, but she still needs a daddy. Don't worry, though; Suzuki twists again. Miyamoto may feel he's the only one who can give her a better life, but as that hospital ending quite clearly tells us, she'll be just fine without him.

ACTUALLY SPECIAL FEATURES: Radiance assembled interesting, if scant, fodder for this release. There’s an interview with critic Mizuki Kodama discussing the gender roles of the film and a presentation of Suzuki’s 1959 short film, Love Letter (which, notably, features the disc’s sole audio commentary). Additionally, Radiance includes its typically stunning reversible sleeve (as ever, I chose the side showcasing the film’s original theatrical poster) and a booklet containing an archival review and an essay, this time from critic Claudia Siefen-Leitich, who analyzes the film’s visuals and shooting disciplines.

RE/PLAY VALUE: As a yakuza revenge thriller, Underworld Beauty takes surprising turns, none so unexpected than the respect it affords its lead female character.

8 / 10

Underworld Beauty is available now. For ordering info, click this.

Directed by Seijun Suzuki.

Written by Susumu Saji.

Cinematography by Wataro Nakao.

Starring Michitaro Mizushima, Mari Shiraki, Hideaki Nitani, Shinsuke Ashida, Kiroshi Kondo, Kaku Takashina, and Toru Abe.