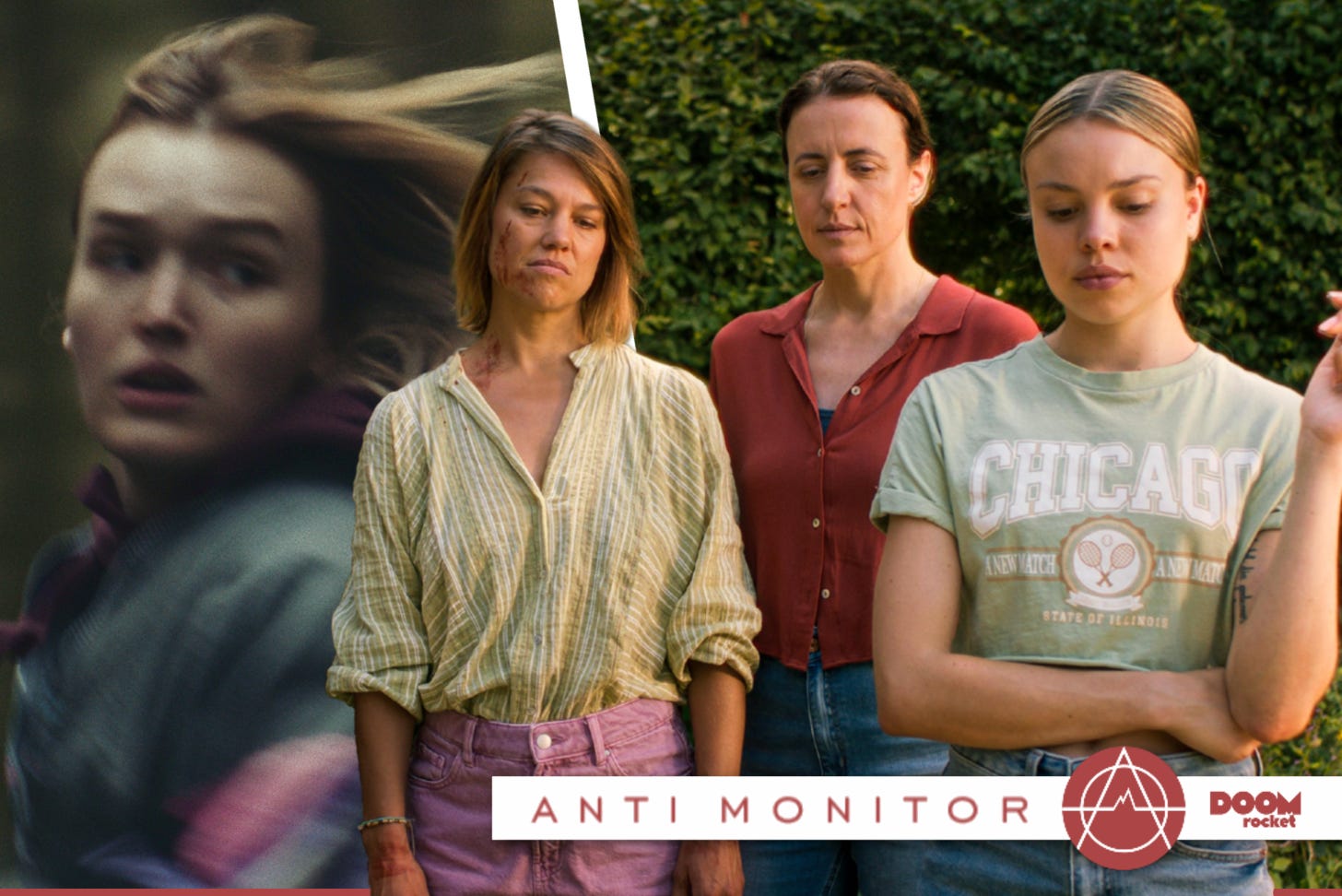

The Sparrow in the Chimney, To Kill a Wolf, reviewed

Two unmissable movies that contrast their angst with a smidge of hope.

THE SPARROW IN THE CHIMNEY

I liked Ramon Zürcher's The Sparrow in the Chimney; it made me angry. It also made me feel sad, wistful, exhausted, riveted, and a host of other knotty emotions besides. A well-populated chamber drama akin to Lawrence Kasdan's The Big Chill, punctuated (pulverized, really) with the surreal, vicious posturing of Darren Aronofsky's mother!, Zürcher's film collects and later scatters the detritus of a family reconvening after years of disappointments and tragedies, weaving a gnarly but no less rich tapestry with it.

Its focus largely centers on Karen (Maren Eggert), a brittle middle-aged mom in the process of separating from Markus (Andreas Döhler), while their three children maneuver to escape her increasingly hostile influence. There's Leon (Ilja Bultmann), the sullen chef/sociopath-to-be; Johanna (Lea Zoë Voss), the blisteringly resentful middle child; and Christina (Paula Schindler), the eldest, already flown the coop and hardened by distance. The occasion is a family holiday at Karen's inherited rural home, where her down-to-earth and vastly more pleasant sister Jule (Britta Hammelstein) arrives with a doofus husband (Milian Zerzawy) and drowsy baby in tow. Wine is sipped, food is supped, and in the murk of evening, memories stir. Danger: here be ghosts.

The Sparrow in the Chimney is the culmination of Zürcher's "Animal Trilogy," and is constructed with the same social claustrophobia as its predecessors, The Strange Little Cat (2013) and The Girl and the Spider (2021). In keeping with those films' emotional intricacies and stolen-glance intrigues, Sparrow takes time to unfold, tossing us into this complex familial dichotomy without preamble. Zürcher presumes the performances and the odd tease of revelation will compel us to keep with it, and presumes correctly. The reward is a deep, if unnerving, engagement with the film's themes: resentment calcified into ritual, generational damage inherited like baubles, warmth and empathy corroded to a featureless nub.

Like a stage play, the film moves while also standing still, frequently diffusing into subplots and peripheral character interactions as people enter and exit rooms, all of which coalesce gorgeously into a bewildering, infuriating whole. Positioning is ever at the forefront of Zürcher's thinking. Take Liv (Luise Heyer), the babysitter who lives in the family cottage adjacent to the larger home; we see her observe the house with all the people milling about, the framing of her longing expression a quietly profound instance that resonates well into the emotionally ferocious finale. The intricate blocking of each scene declares the dynamics of the moment, while establishing the lived-in texture of the film's setting: a mausoleum limned with sunshine, where the doors do not lock and the kitchen window hangs open for butterflies and people to come and go at will, including the wee sparrow that lends itself to the movie's title. Such warmth and beauty rarely feel so forbidding.

It should be noted that the sparrow escapes its eponymous prison, a symbolic, hopeful gesture to cling to when the story later shifts into surreality and lets the heat rise. Zürcher folds his entire film into this image: the fleeting beauty of a bird breaking free from its suffocating prison, shaking off the ashes of confinement as wings take flight. When the film later slams a door during an appalling act of cruelty, it's tempting to ignore the sparrow's thematic beauty. The scenes that follow inflict pain because we anticipate what's coming, just as we fear that the film's earlier offering of grace was hollow. Hang on; all this suffering is a blunt-force reminder that abuse has an echoing effect, that anger passed down through generations is cyclical. The rage that manifests can be monstrous, as it is here. Yet Zürcher still manages to close on a paradoxically optimistic note, stating quite plainly that something so hurtful and ingrained can't be fixed, only purged. The irony is that the ensuing catharsis leaves its own scars.

9 / 10

The Sparrow in the Chimney opens in limited release beginning on August 1. For more info, click this.

Written and directed by Ramon Zürcher.

Starring Maren Eggert, Britta Hammelstein, Luise Heyer, Andreas Döhler, and Milian Zerzawy.

117 mins. / Unrated. Those who cherish their pets, beware.

TO KILL A WOLF

Kelsey Taylor's To Kill a Wolf is a well-performed, confidently directed feature debut that searches for meaning in grief amid the grey expanses of the Pacific Northwest and, gradually, finds it. Once the film stakes out its fabulist conceit — a contemporary retelling of Little Red Riding Hood, sectioned into four mist-wreathed chapters — it begins to gather an interior momentum that braces its two leads against the gravitational undertow of despair, always present and ready to consume. It follows Dani (Maddison Brown), a hooded, haunted 17-year-old runaway, pursued by regret and a host of other complicated emotions, who, in her exhaustion, is discovered in hiding by a lonely man in the woods who carries more than a few burdens of his own.

I say lonely, but "isolated" is a better word. This fellow (Ivan Martin), filling the Woodsman role, has intentionally severed himself from his community. Taylor wisely withholds the specifics of his retreat and Dani's flight long enough for an ambiguous rapport to form between them. In the tentative accommodations they make — his offering of shelter, her choosing to accept it — we begin to grasp an interiority beyond their spiritual wounds. Emotional terrain reveals itself through gesture, hesitation, and silence. We realize they need each other, only not for the reasons we might expect.

While To Kill a Wolf isn't a trauma contest, it is Dani's story that propels the film. In chapter two, when the woodsman ferries her over the river and through the woods to grandmother's house, Taylor reveals, with acute emotional calibration, the contours of her despondency. A flashback sequence makes explicit what was before merely suggested: Dani has fled from her aunt (Kaitlin Doubleday) and uncle (Michael Esper) for reasons that make the film's theme of shattered trust snap into sharp, devastating focus. The chapter is rendered with aching clarity and calls to mind India Donaldson's Good One, a similarly small movie with enormous swells of feeling in which a young girl approaching adulthood faces the disappointment of people without anyone to shield her from the soul-rending fallout.

From here, a delicate balance is struck. Taylor doesn't overwhelm the flashback with melodrama, but she doesn't shy away from the devastating breach it contains, either. As the film shifts into chapter three, "The Wolf," we grasp the nature of Dani’s situation, where intellectualism has been warped into a tool to manipulate her growing and curious mind. Almost instantly, this quiet, discreet story shifts its axis and becomes something larger and more devastating.

To Kill a Wolf carries us through the woods. Taylor's storytelling instincts fortify the film with an uncommon wisdom and dignity, and the trust she places in her actors pays dividends; she frees them to fill the sparse environments with subtleties and nuances that make the film sing. Martin's a sturdy presence; his hangdog expressions, set under a mop of unkempt hair and a shaggy beard, chart the dull ache just behind his nervy gaze. Brown is astonishing, a tangled knot of emotions that pulls tighter by the minute until catharsis comes and Dani can finally, mercifully, unspool. We enter this story as two disparate paths intersect, and the epiphanies these characters reach while in parallel, however fleetingly, feel like a miracle. Hurt never goes away. But as Taylor reminds us, given time and a bit of help, it can change into something new, something useful.

8.5 / 10

To Kill a Wolf starts its national theatrical tour at Regal Union Square Stadium 17 in New York on August 1. It screens at Regal City North 14 in Chicago on August 22. For more info, click this.

Written and directed by Kelsey Taylor.

Starring Maddison Brown, Ivan Martin, Kaitlin Doubleday, Michael Esper, Dana Millican, and David Knell.

92 mins. / Unrated. Contains difficult sequences of despair.