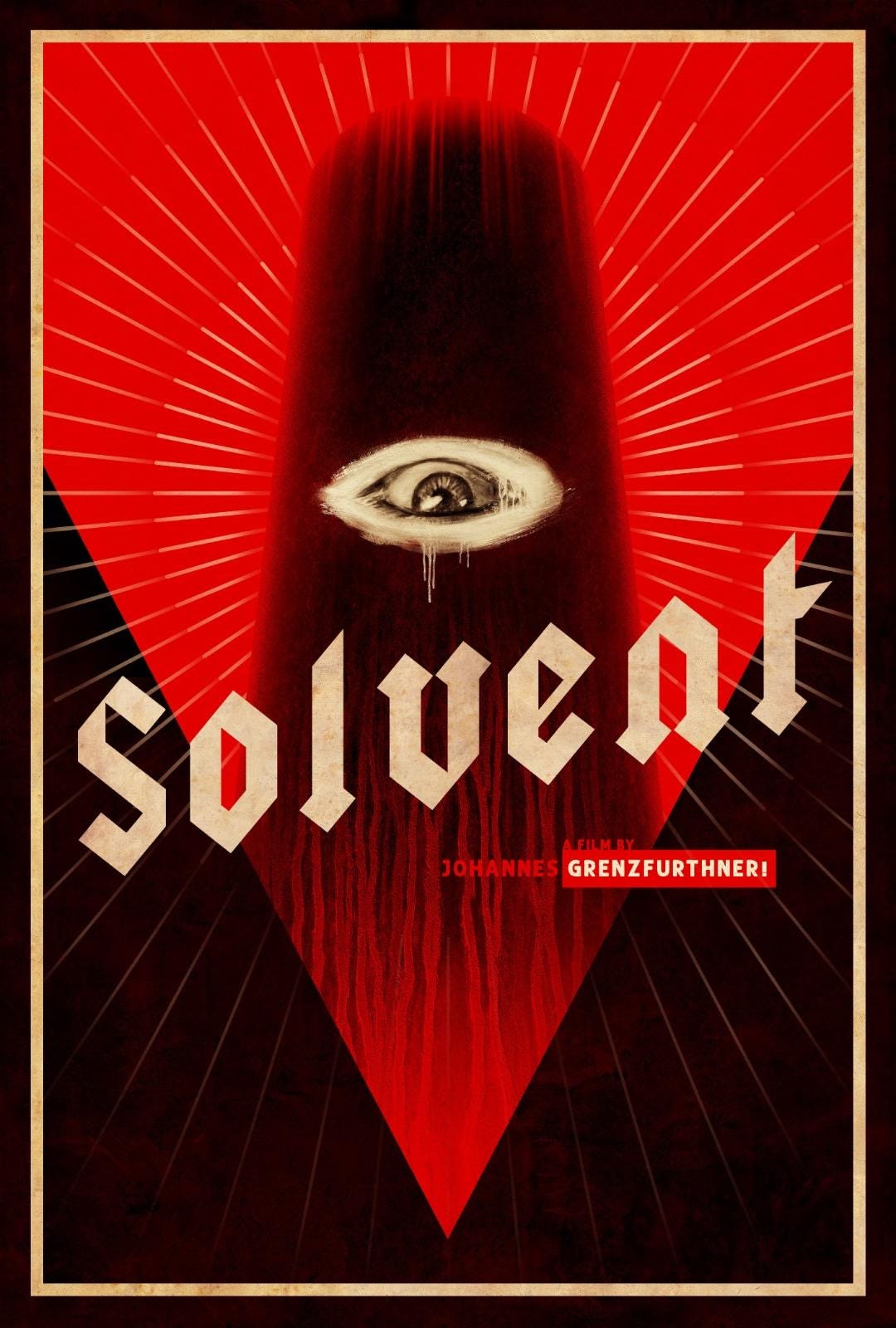

POV horror Solvent blurs its view on fascism

Though Johannes Grenzfurthner's experimental terror tale has enough to appreciate.

Can I talk shop with you for a minute? Solvent is the kind of movie that is a dream to review and a nightmare to rate. Austrian filmmaker Johannes Grenzfurthner has tossed a cinematic nailbomb into the discourse, and the wild spray of shrapnel affords critics plenty of grist. We have a motion picture full of deliberately idiosyncratic stylistic choices, wild tonal swings, and an oppressive sense of relevance and urgency. We have a work that walks a fine line between art and exploitation and that flirts with some morally questionable sentiment (more on that later). All of this ensures I’m not going to have any difficulty reaching my word count. But… does it work? Do its pieces come together to form a final project worthy of the ambition that spurred its creation? Did I like this?

Solvent is a found footage horror centering around Gunner S. Holbrook (Jon Gries, Uncle Rico from Napoleon Dynamite), a veteran of the first Gulf War now leading a small team of contractors who appear to specialize in searching for historical artifacts. Holbrook, along with Polish academic and on-again/off-again romantic partner, Krystyna (Aleksandra Cwen), and her colleague, Cornelia (Jasmin Hagendorfer), is tasked with searching a home in rural Austria that belonged to Wolfgang Zinggl, a presumed-deceased farmer and former SS officer. The group has been assembled as a sort of PR stunt by Zinggl’s grandson, Ernst (Grenzfurthner himself), with the intention of locating any documentation pertaining to the Holocaust that Zinggl may have kept from the war. This seemingly straightforward job falls apart, however, when the group discovers a hidden alcove where a pipe juts from deep beneath the earth. From there, tragedy ensues. The events leave Krystyna in a state of nervous breakdown and Holbrook obssessed with understanding what happened.

Grenzfurthner’s earlier film, Masking Threshold, provides a sort of template for Solvent. Both works are shot and edited like YouTube video essays. Solvent is explicitly framed as Holbrook’s video diary, shot almost entirely from his perspective (Gries’s face is rarely visible on camera). Scenes are often interrupted by smash cuts to documents, home video recordings, and, increasingly as the film wears on, stock footage from World War II and the Holocaust. Editor Anton Paievski floods the screen with the detritus of a century of mechanized brutality in an effort to simulate Holbrook’s deteriorating grip on his sense of self. Also carried over from Masking Threshold is Grenzfurthner’s affection for dick trauma and his ability to craft stomach-churning imagery while keeping the most explicit violence off-screen. But Masking Threshold was an insular, claustrophobic portrait of a rational mind coming unmoored from reality, whereas Solvent examines that epistemological decay writ large on a societal scale.

I don’t want to get too deep into spoiler territory, but suffice to say that Grenzfurthner conceptualizes fascism and white supremacy as a kind of pollution or contaminant — a corrupting influence upon the elemental forces that circumscribe our existence. Something that infects us from without. I appreciate, also, that he broadens his critique of imperialism beyond the soft target of Nazi Germany to include the United States. Holbrook is the discarded veteran of a foreign war fueled by US Imperialism and the son of another. Vietnam left Holbrook’s father emotionally crippled, just as Holbrook’s own experiences in Kuwait drove him into mercenary conflicts that were even more brutal and lawless. State-sanctioned violence, both at home and abroad, is a suffocating miasma.

Grenzfurthner’s grasp on the scope of political atrocity in the 20th and 21st centuries is what makes it so disappointing that he seems unwilling to apply that insight to the ongoing situation in Gaza. Solvent makes two references to contemporary Palestine, both from the mouth of Zinggl, and both implying some symmetry between the German National Socialist movement and the current efforts to end the Palestinian genocide. A charitable reading of these remarks is that antisemites can Trojan Horse their bigotry inside legitimate critiques of the state of Israel (see: Candace Owens and Marjorie Taylor Greene). A much easier conclusion to draw, however, would be that support for Palestine itself is a bad-faith rhetorical trap set by Nazis. I’m curious how Grenzfurthner’s perspective on these matters has changed in the year-plus since Solvent was completed, since the enforced starvation in the Gaza Strip, the assassinations of so many reporters and aid workers, and the criminalizing of protest and dissent in allied states like the US and UK. It nevertheless remains disappointing that a film that so deeply engages with the persistence of fascism and genocidal violence into the 21st century handles the most blatant genocide of my lifetime in such a careless manner.

Leaving aside the moral dimensions, the more practical elements of the film present some highs and lows. Aleksandra Cwen’s performance as Krystyna was a clear standout for me. Her voicework freak-outs during phone calls with Holbrook are bone-chilling. I thought I was going to have problems with Gries’s Holbrook. He comes across in the film’s first act as a kind of cheerful bully, such that I was dreading the prospect of spending the next 90 minutes in his head, but he emerges from the film’s early turning point considerably humbled. Gries does an excellent job conveying Holbrook’s haunted bravado with just line readings and gestures. The only actor I struggled with was Grenzfurthner as Ernst, Zinggl’s wormy descendant. His performance has a comedic, tonally dissonant broadness that never fully became funny to me. Additionally, despite the editing maintaining a sense of momentum, the film sometimes struggles to externalize its conflict. The primary conflict of Solvent unfolds inside Holbrook himself, where a more conventional film might depict this through hallucinations or other terrors seen from the main character’s perspective. The restrictions of this found footage format limit us to only what the camera can perceive, leaving us with a climax that largely consists of Holbrook talking to himself.

Despite my criticisms, I do like Solvent quite a bit. I like that Grenzfurthner is a filmmaker preoccupied with the most urgent questions of our time and that he approaches them via the strange visual vernacular of the extremely online. Grenzfurthner places himself among an emerging breed of lo-fi horror maestros who craft new nightmares from our digitally mediated experiences, including figures like Jane Schoenbrun, Kyle Edward Ball, and Robbie Banfitch (with the latter two explicitly referenced in Holbrook’s crew as “Kyle Edward Boll” and “Richie Fichvogt”). I can only hope his future work continues to wade dick-deep into the epistemic cesspool of our age.

7 / 10

Solvent hit VOD and Digital platforms on October 10. For more info or to learn where to watch, click this.

Directed by Johannes Grenzfurthner.

Written Johannes Grenzfurthner and Ben Roberts.

Starring Jon Gries, Aleksandra Cwen, Johannes Grenzfurthner, Roland Gratzer, Jasmin Hagendorfer, and Ronald von den Sternen.

94 mins. / Unrated. Get ready for smatterings of gore and sailor talk, plenty of nazi stuff, and just so, so much dick trauma.