Kill Your Boyfriend is a comic bombardment of nihilistic exuberance

In 1995, Grant Morrison and Philip Bond chose anarchy.

This is RETROGRADING, where we live for art and art is violence.

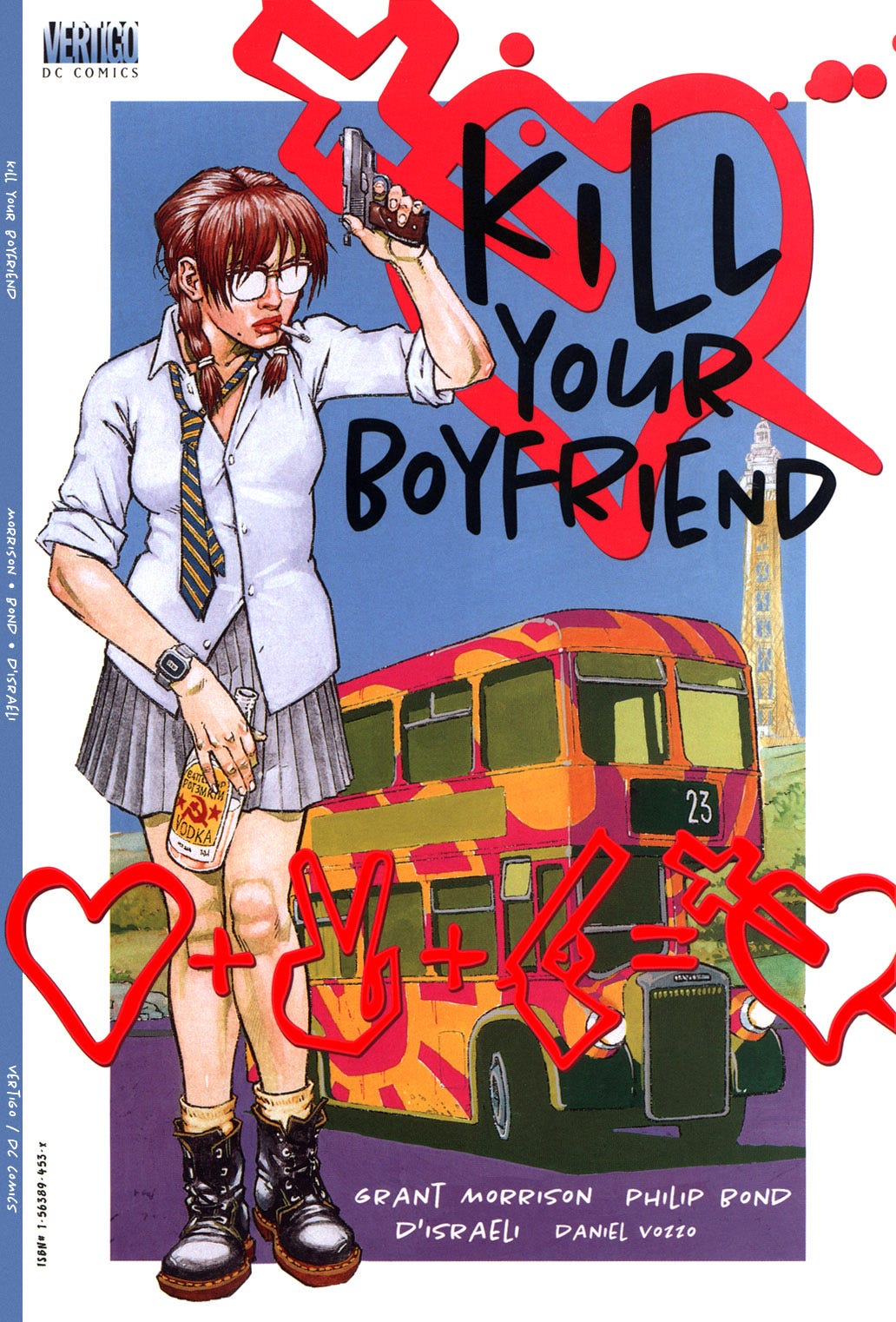

THE COMIC: Kill Your Boyfriend

THE YEAR: 1995. Having emerged from a loose-knit group of books edited by Karen Berger, DC's "Mature Readers" imprint Vertigo has been officially up and running for two years. Grant Morrison, the Scottish writer of Doom Patrol and Arkham Asylum, is one of its biggest stars.

THE SPECS: Written by Grant Morrison; penciled by Philip Bond; inked by Bond and D'Israeli; colored by Daniel Vozzo; lettered by Ellie DeVille. Published by Vertigo/DC Comics. For Mature Readers.

THE MAKE: Grant Morrison's life story is famously loaded with bizarre, larger-than-life details that go a long way towards explaining their facility with superheroic adventure and mind-melting science fiction. Their father was an anti-nuke protester who broke into government facilities. In the early Eighties, they dressed like Austin Powers and played in a band. They're a practicing chaos magician. During the Nineties, they spent the royalty money from writing a hit Batman graphic novel on partying and traveling the world, all while ingesting heroic amounts of hallucinogens. Allegedly, they were abducted by interdimensional aliens during a trip to Kathmandu. Frankly, Morrison's life is cooler than most comic book writers, and they have a fair share of rock stars beat, too.

Morrison has told and re-told these stories, and the internet rumor mill is always happy to embellish them further. But people often forget that before Morrison was a globe-trotting comic book superstar shaman, they were almost normal. Teenaged Grant was just another lonely, sexually frustrated nerd, whiling away the days under the rainy gray skies of Thatcher-era austerity. But, determined to escape the stultifying confines of working-class life in Glasgow, they created a new persona as a psychedelic dandy and steadily worked their way into the comic book industry. After years dying to break free from the regimented boredom of school, most of us find ourselves equally trapped by unrewarding jobs. Instead, Morrison freed themself by seizing the "means of expression" to create art that would, in turn, hopefully, help others to free themselves.

Following stints writing for Marvel UK and the Doctor Who comic, Morrison created Zenith for 2000 AD in 1987. A year later, they were recruited to DC. Following Alan Moore's many comics successes and UK writers becoming a hot commodity in the industry, editor Karen Berger flew across the pond on a talent-scouting expedition. Morrison successfully pitched an animal-rights-centric reinvention of the third-stringer hero Animal Man, and when the book did well, they followed up with an absurdist reboot of Doom Patrol before penning Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, a bestseller. The audience for more adult and experimental comics was growing, and Morrison stood at the forefront, waving their freak flag high.

When Vertigo launched in 1993, Sebastian O from Morrison and Steve Yeowell was one of the first books out of the gate. Originally slated for Disney's aborted adult comics line Touchmark, editor Art Young brought the project to DC; two years later, Young edited Kill Your Boyfriend. In typical jetsetting fashion, Morrison wrote KYB while traveling across New Zealand, inspired by the myth of Dionysus and the Maenads, the darkly hilarious plays of Joe Orton, and the Terence Malick film Badlands, itself inspired by the murders committed by Charles Starkweather and Caril Fugate. The script was fully formed when it went to artist Philip Bond, who'd already popped his Vertigo cherry with a few issues of Shade, The Changing Man. The final product was lobbed into unsuspecting comic shops as a one-shot in 1995, a fifty-six-page grenade with the pin pulled. It blew minds.

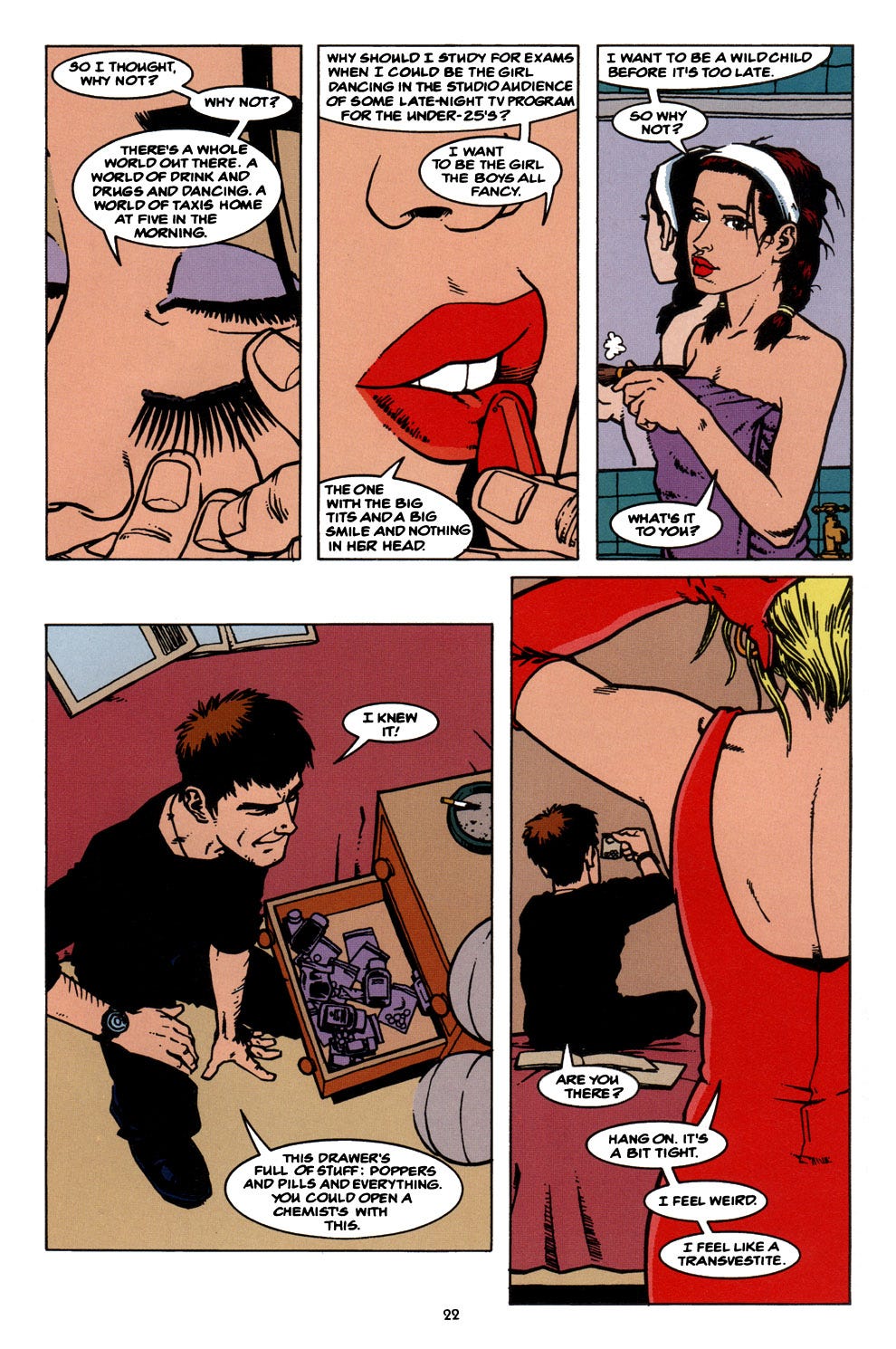

THE REVIEW: The stars of Kill Your Boyfriend have no names. They are the Girl and the Boy, two platonic ideals of teenage rebellion. In the beginning, the Girl is trapped in the amber of ordinary life, going to school, suffering the indignities of homework, and wishing her dull, fantasy-novel-obsessed boyfriend would at least try to have sex with her. Meanwhile, her parents are convinced she's already sleeping around, and her frustrations are channeled into daydreams of violent retribution. But when she meets the Boy, all her dreams come true. The Boy, introduced brazenly stealing a man's cigarettes, is the epitome of cool: a good-looking, loudmouthed criminal with zero respect and nothing to fear.

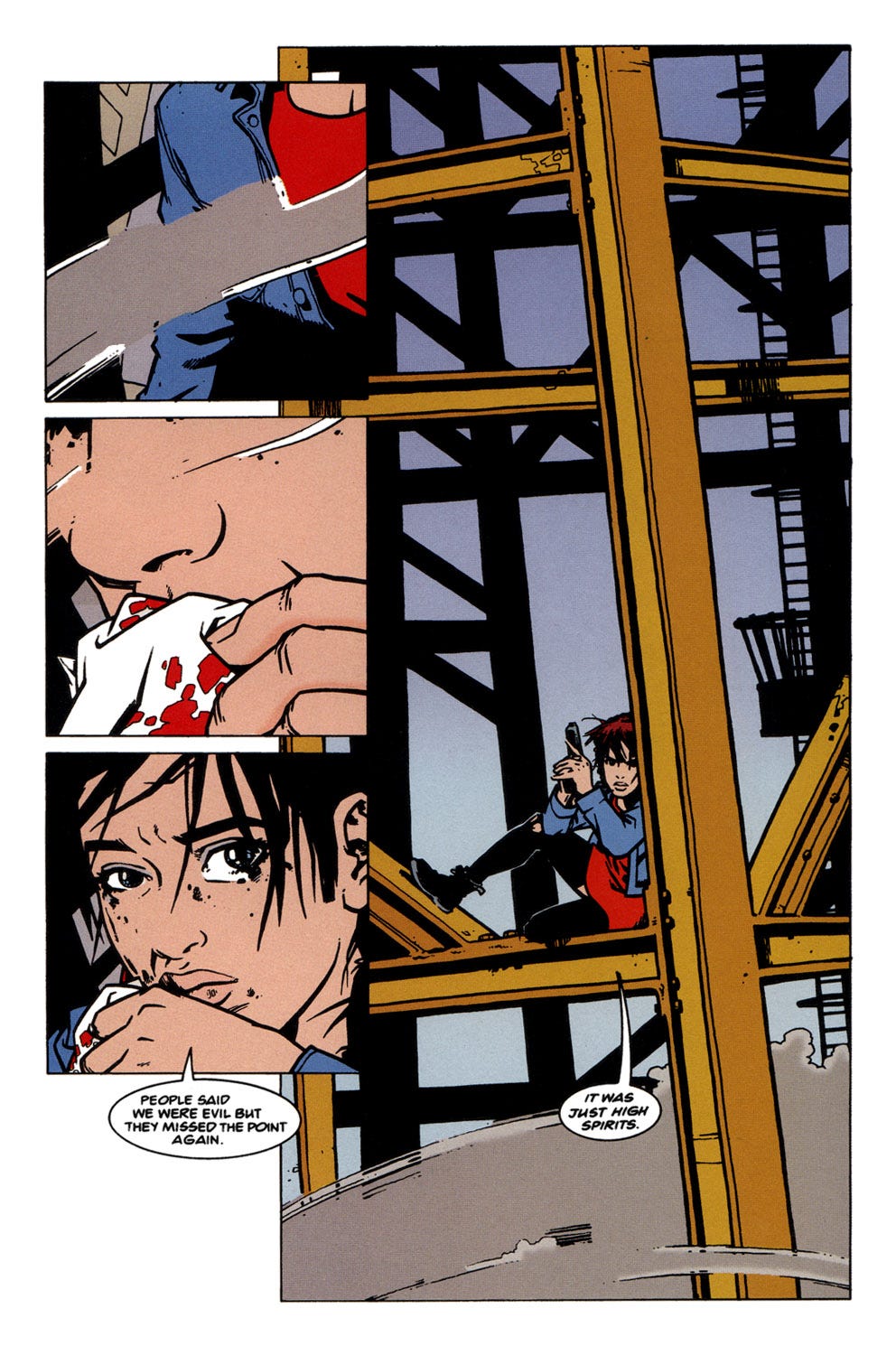

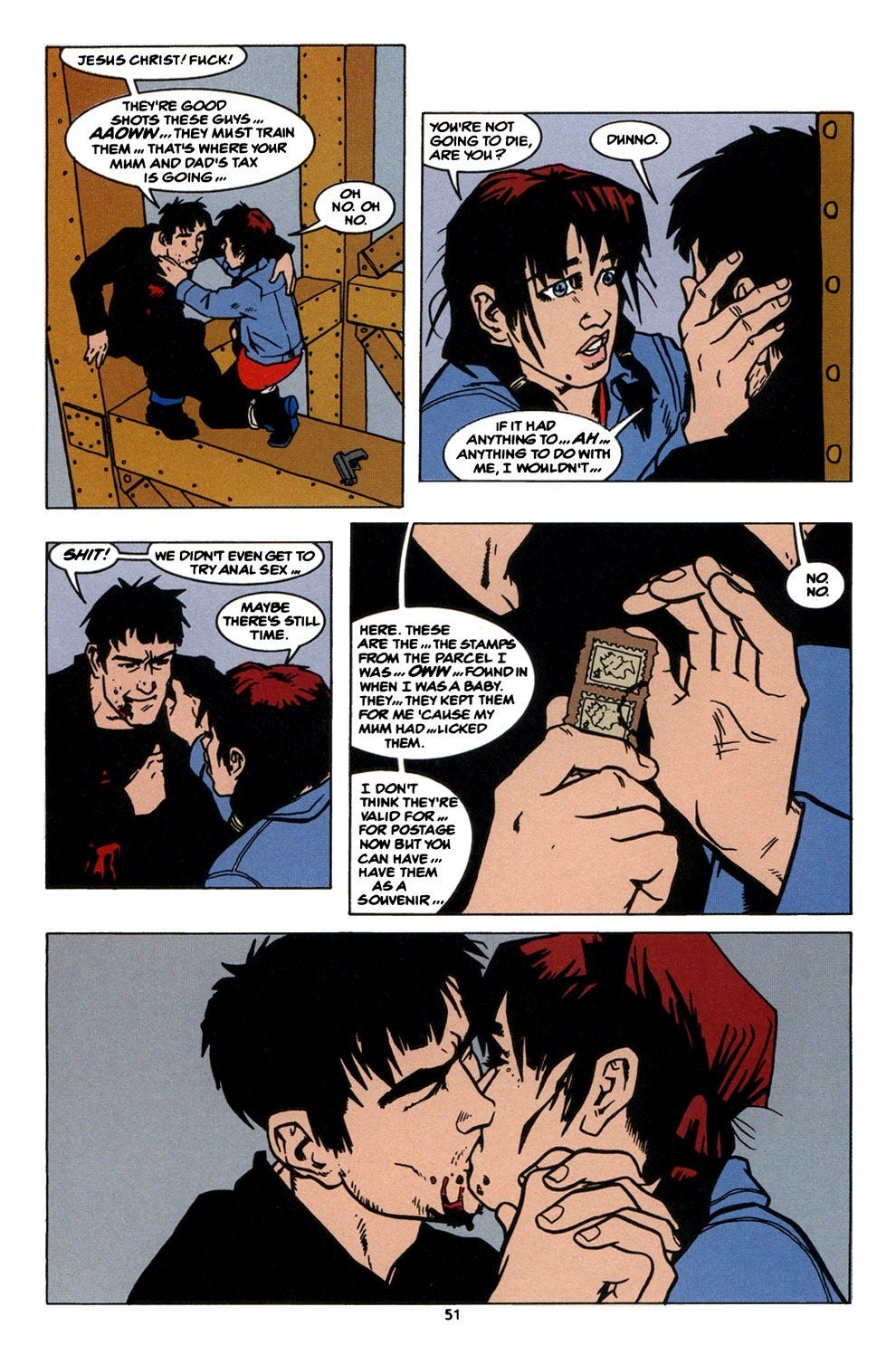

True love doesn't wait. Within the instant that they've met, the Girl has taken her first drink, leading immediately to her first act of vandalism, following which she stands by in mute admiration as the Boy dispatches her now ex-boyfriend in a comically unnecessary hail of bullets. Before the night is out, they've also killed a cross-dressing conservative politician, taken Ecstasy, and she's had sex for the first time (turns out, sex is great!). All of this anti-social activity is served up with a heaping spoonful of ironic detachment — it's clear that we're not meant to take the heartless ultraviolence too seriously. That's the delivery mechanism, not the message. Of course, teenagers understand that instinctively, and if their parents don't, then shocking them is part of the fun.

Philip Bond is the perfect artist for these hijinks. Spawned from the same punk-infused alternative British comics scene that gave rise to Tank Girl, he knows how to find the humanity humming underneath the carnage. Daniel Vozzo's bright, flat colors accent the bold, energetic linework. Facial expressions move easily from over-the-top to naturalistic, and Bond chooses his moments well, accentuating both the comic timing and flashes of vulnerability in Morrison's script. And it's a hell of a script. Short, punchy scenes roll into one another, the story surging onward like a rush of hormones. Morrison packs ideas into every panel. Occasionally, there might be too many ideas at play — one revelation buried in the third act is more distracting than anything else — but as busy as the story is, it still goes down light and frothy, a good lager.

The Girl delivers lines directly to the reader, providing a running monologue that simultaneously vents her angst and expounds on the story's themes. It has the effect of the traditional thought balloon given a Nineties cinema update. Storming away from a fight with her parents, a universal experience if ever there was one, she wanders around town, saying, "I hate all these faces… I feel sick, unsavable." Later, in KYB's equivalent of a mild-mannered reporter stepping into a phone booth and emerging as an alien god, she abandons her plain clothes and auburn pigtails in favor of a red dress and a blond wig. Anticipating the reader's criticism that she's turning into a bimbo, she embraces it, insisting that she's not real anymore. As a figment of the Boy's imagination, she's free to do anything.

In real life, we probably shouldn't go around shooting and robbing people, even if they are old and boring. After all, forensics has gotten really good these days. But in our imaginations and art, we're free to explore all of the possibilities of who and what we can be, to change our beliefs and personalities as easily as we change clothes. The malleability of the self is a theme that runs through nearly all of Morrison's work; trying on new identities is part and parcel of adolescence and often adulthood, too. So go ahead. Be someone new today. You might like it.

NOSTALGIA-FEST OR REPRESSED NIGHTMARE? Kill Your Boyfriend is a three-minute punk single in comic book form, packed full of nihilistic exuberance and terrible decisions that feel great. Give it a spin.

RETROGRADE: B+