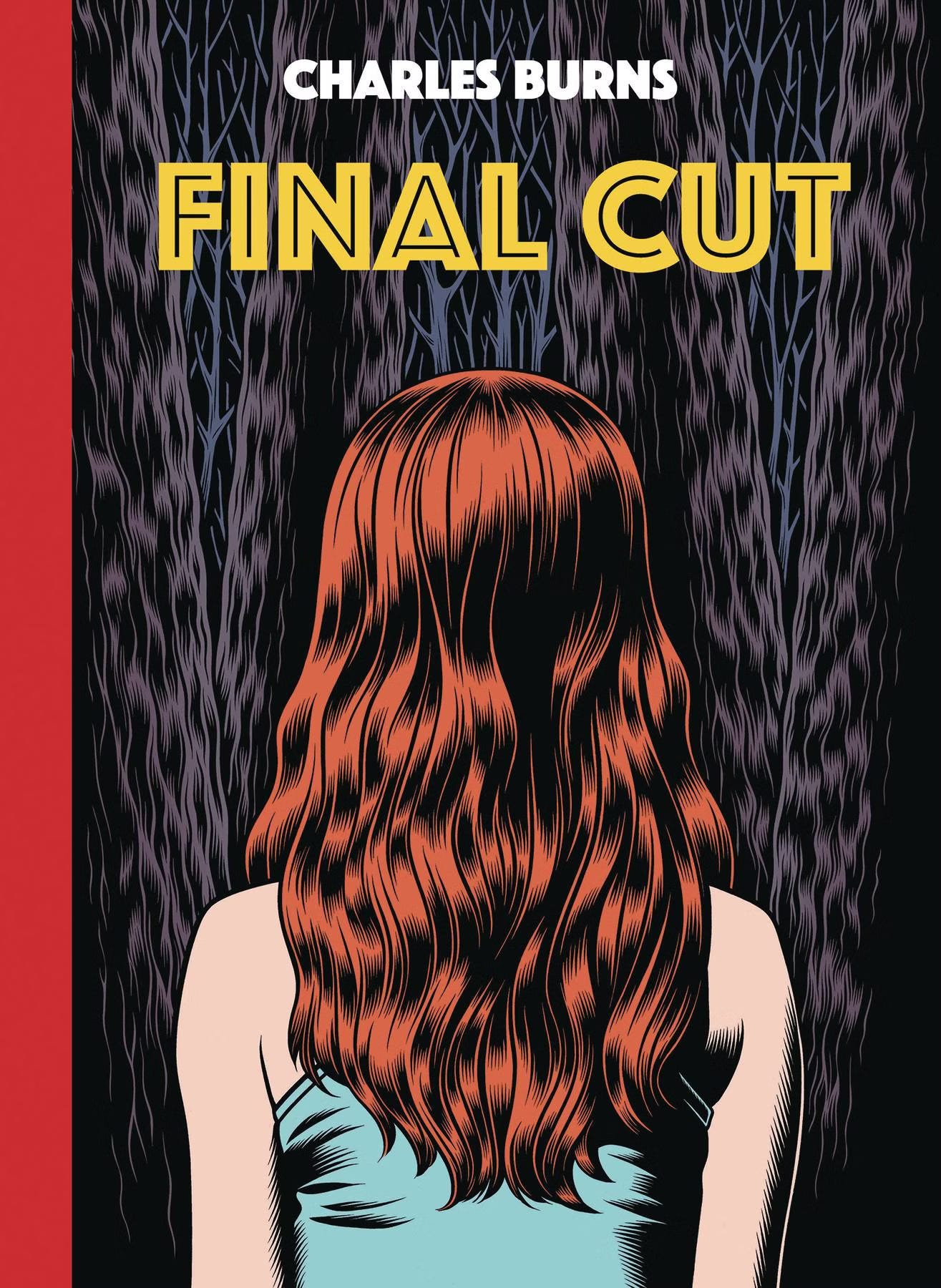

Final Cut Review: Charles Burns takes us to the movies

The artist's latest is thematically rich and dramatic — just don't compare it to Black Hole.

Like most fine artists, Charles Burns spends a lot of time in his head, but his gift is knowing how to pull us in there, too. Look at Black Hole, which deployed post-adolescent longing and disillusionment as a means to disarm the reader, only to then toss us into a psychotropic tailspin of body horror, murder, and spiritual reflection. It was rough play, but I submitted to Black Hole willingly and was moved/unnerved by the epiphanies made by its characters on the crest of chaotic change and cosmic indifference. Charles Burns makes cerebral apocalypse comics, and I like them.

Burns's skill in sustaining atmosphere also does serious heavy lifting. It's the way he abstracts the regular stuff. Thick brushes, fine details, odd faces, the foreboding natural world, it all fuses into an inky miasma of strange beauty and unease. Burns is a singular visualist and a peculiar storyteller; sense memory colors his comics, but they (and we) are often at the mercy of the darker creative impulses that dwell in the deeper crevasses of his mind. But he can be playful, too! Check out his punk-infused Last Look trilogy (X'ed Out, The Hive, and Sugar Skull), which tapped into Hergé's wavelength and inverted/perverted Tintin to scandalizing, sometimes bewildering effect. And if Last Look was Burns-as-punk, then Black Hole, and now Final Cut, find the artist blasting grunge: moody, introspective, mercurial, emotionally upsetting.

I'm worried the conversation around his much-anticipated return to longform graphic storytelling will pit readers' expectations against artistic intent. Final Cut isn't nearly as mesmerizing as Black Hole in its best moments, but that isn't the point. Final Cut rejects comparison, almost stifles it with its uniqueness, which frees up Burns to work his thematic mojo over us. Horror and sci-fi aren't its genres but influences; for example, Burns uses Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) as a Rosetta stone to help us better understand his themes of identity, perception, and creative doom. This book wants to disturb us, and to some degree, I say it succeeds. If nothing else, it should make creative types squirm.

Film is the driving force behind Final Cut. The passion we have for it, how it becomes a defining part of our identity, the way we want to share our favorites with the people we like, that's all in here. Its ideas about shared cultural experiences and the difficulty of articulating art, even to our peers, are sweet and awkward — ideas which, under Burns's demented pen, become creepy soon enough. But Burns isn't satisfied with merely leaning on the visual language of horror or science fiction to freak us out; his goals are more dramatic. Final Cut is not Black Hole, and embracing that before going in benefits the reading. "If I'd been smart, my marketing strategy would have been Black Hole 2," Burns told Publisher's Weekly in July. Thank goodness he's playing dumb.

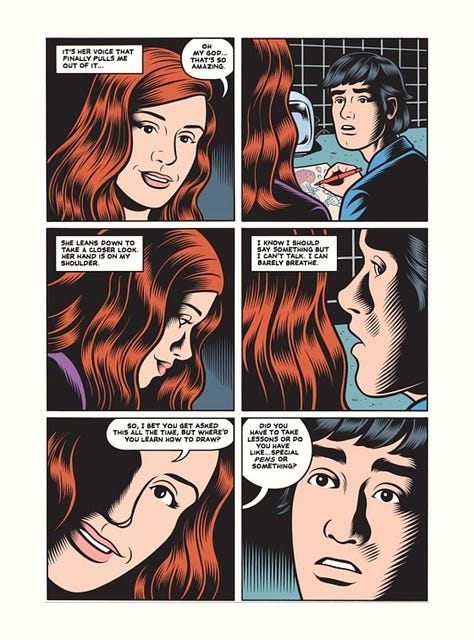

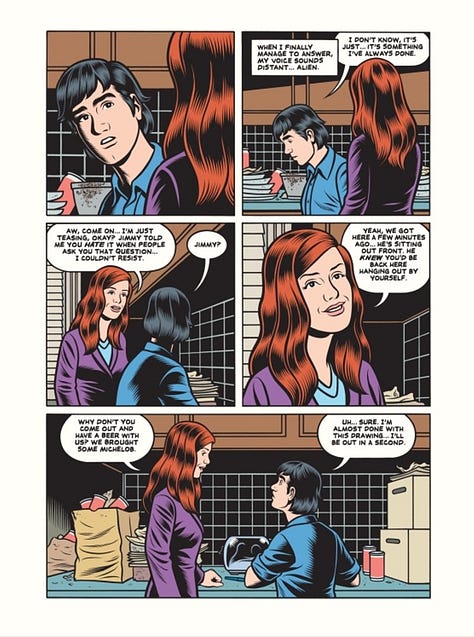

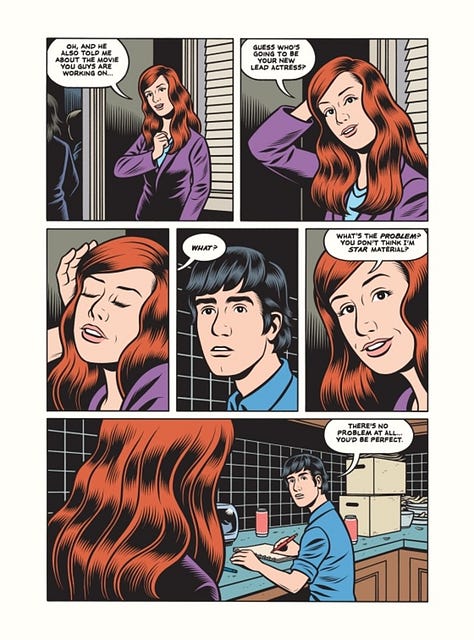

With isolation and depression as its significant themes, Final Cut dwells on those overwhelming interior thoughts that alienate us. It's about those who observe (or gawk at) people but, in their isolation, can't adequately read a situation or see folks for who they are. This brings us to Final Cut's lead character: meet Brian, a brooding artiste who draws furiously into his notebook and shoots home movies with his easy-going buddy Jimmy. You feel that Jimmy's in the film game to have fun. Brian does it to make sense of the world, evade trouble at home, and/or examine his darker notions. They're interesting foils for each other, though Burns doesn't really delve into their contrasting artistic objectives.

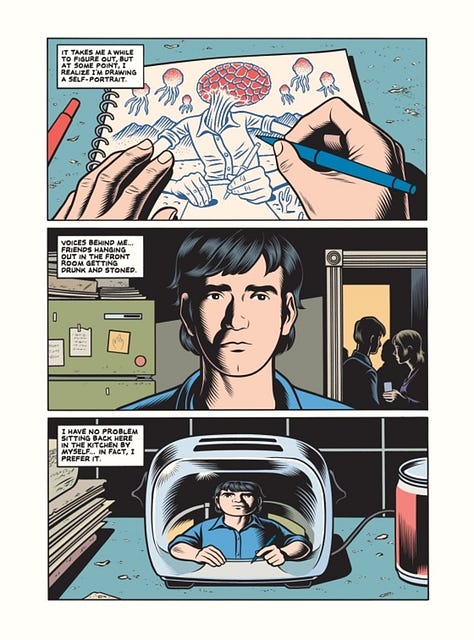

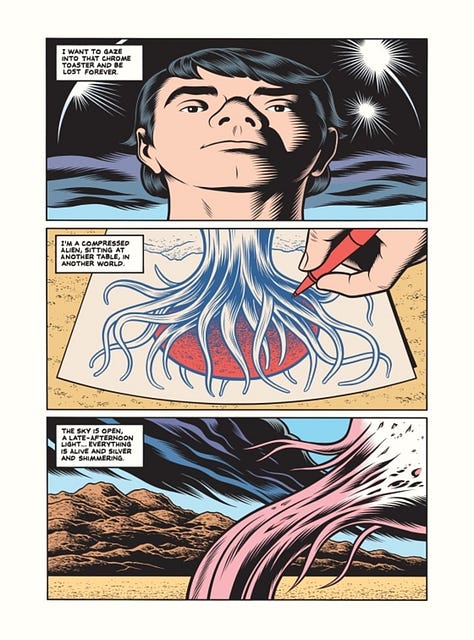

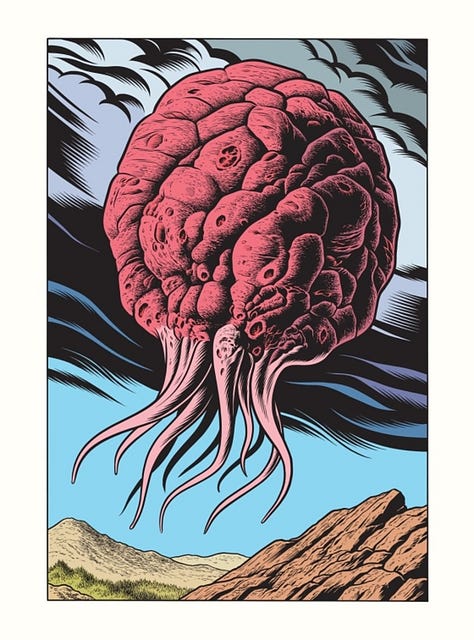

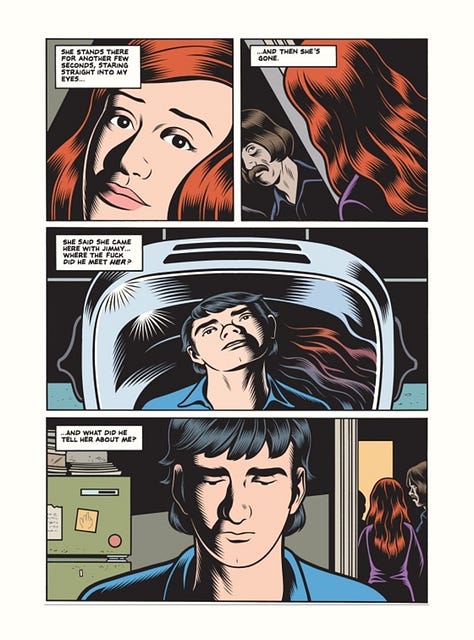

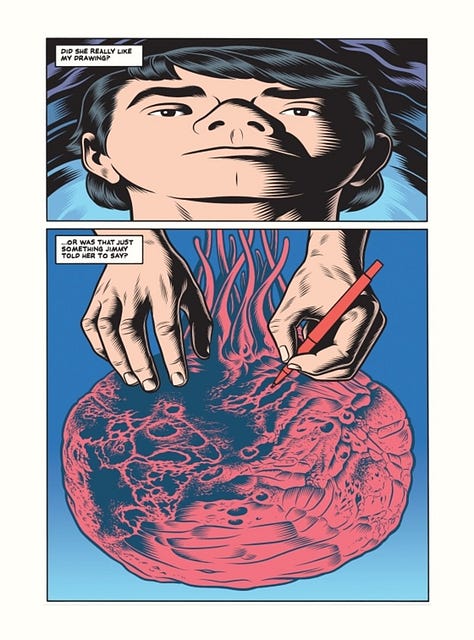

Instead, Final Cut is half focused on Brian's creative vision, a mental plane of alien dream existence he describes as "alive, silver, shimmering," where, in some instances, he takes the form of a fleshy hot-air-balloon-looking thing (I think). In other moments, he floats around in the buff. These surreal dreams inspire him during his latest project with Jimmy to the overwhelming degree that it feels like they're making two different films. While Jimmy goes with the flow during their homemade production, Brian gets stuck on the kind of bizarre thoughts we have when we've taken a bit too much of whatever, sitting in a crowded room of similarly addled folks, stupefied by what we're seeing and thinking. For those who've experimented with drugs, these thoughts can pop up again when we're otherwise lucid. For Brian? They screen behind his eyes in a marathon loop.

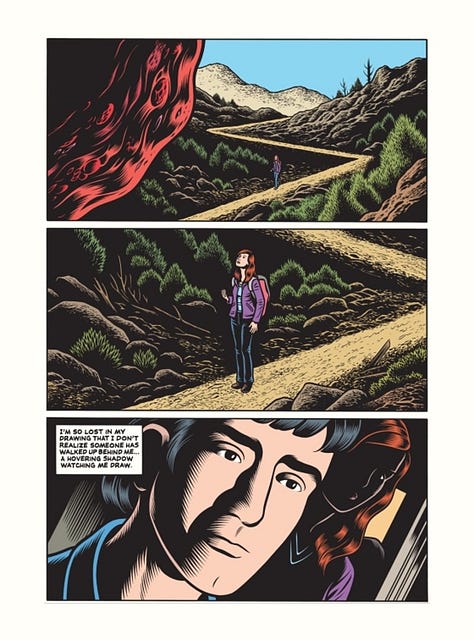

It's a bummer to have an interior critic bombing around your mind all the time. Brian's are so omnipresent they ought to ask for a salary. "Can't you come up with something original?" one avatar asks when his invigorating flying dream morphs into an obvious reference to Body Snatchers. Brian's mental companion in this instance is Laurie, a girl he met in waking life to whom he's quite attracted. Since he's an adolescent dreamer, he inevitably visualizes her naked, and Dream-Laurie comments on this, too. Burns also hops on the critical bandwagon; there's a panel where Brian's struck by a beautiful moment with Laurie during a mountainside shoot, and he asks himself, "How do you make time stand still?" You're the one holding the camera, my man.

When it comes to interior criticism, Laurie is Brian's equal. She knows she's too eager to please, which is how she wound up starring in Brian and Jimmy's movie. Laurie doesn't torture herself as Brian does; we know this because Burns splits each chapter into sections where we oscillate between Laurie and Brian's points of view. This provides a third perspective on their quasi-romantic-but-not-really friendship: our own, which is Final Cut's strongest function. By letting us observe two conflicting thought processes about who these people are to each other, we can interpret the closest approximation of the ugly truth. It doesn't look too good for Brian, who obsessively frames Laurie as an ethereal screen idol both on page and screen. She's his muse — just don't tell her that.

It's easy to fall into Final Cut's headier aspects. Burns renders widescreen point-of-view panels during Brian's reveries, unnervingly harnessing human perspective to make it feel like we're there. His skill with textures remains immaculate: images of flora and stone have surfaces that seem to shift as if our minds have been laced with the dreaded lysergic; hulking masses that resemble patched flesh hover above the horizon line, compelling us to peer even closer at the page to understand just what the hell is going on. Burns's landscapes are almost prehistoric, accentuated by ancient cracks in the earth that spread out into eerie configurations. Foliage is everywhere, Bob Ross-like, with unhappy little trees serving as a canopy over Brian and Laurie's uncomfortable melodrama.

One of my favorite bits in Final Cut, and what will compel me to pull it from my shelf again, is a bit when Burns diligently recreates scenes from Body Snatchers as Brian and Laurie have the worst movie date ever. The juxtaposition of the film's hostile, forbidding images with the chilliness we observe in Brian and Laurie's body language folds Burns's ideas of art and creativity into a paranoid, surrealist nightmare. The imagery is beautiful (I didn't mention Burns's take on The Last Picture Show, which serves a similar if sadder thematic purpose), an "every frame a painting" tribute to a sci-fi marvel and a grim window into how Brian thinks, creates, and sees people. Or doesn't see, as seems to be the case.

Later, when Laurie evokes the phrase "pod people," we're not thinking of Body Snatchers so much as the sketch Brian showed her just before they entered the theater — it's a pod, open and empty, which to Laurie resembles a "big vagina." When I read that, I cackled. It's a phrase Laurie uses to comment on his work, possibly there as insurance for Burns against any fresh criticisms regarding one of his more, um, recurring visual motifs. Like most fine artists, he is nothing if not self-aware.

8.5 / 10

Final Cut is in bookstores now. To snag a copy of your own, click this.

Pantheon Books / $34.00

By Charles Burns.

Check out this 10-page preview of Final Cut, courtesy of Pantheon Books: