Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller is a journey of cognition via comics

Joseph Lambert's form-busting biography makes pupils of us all.

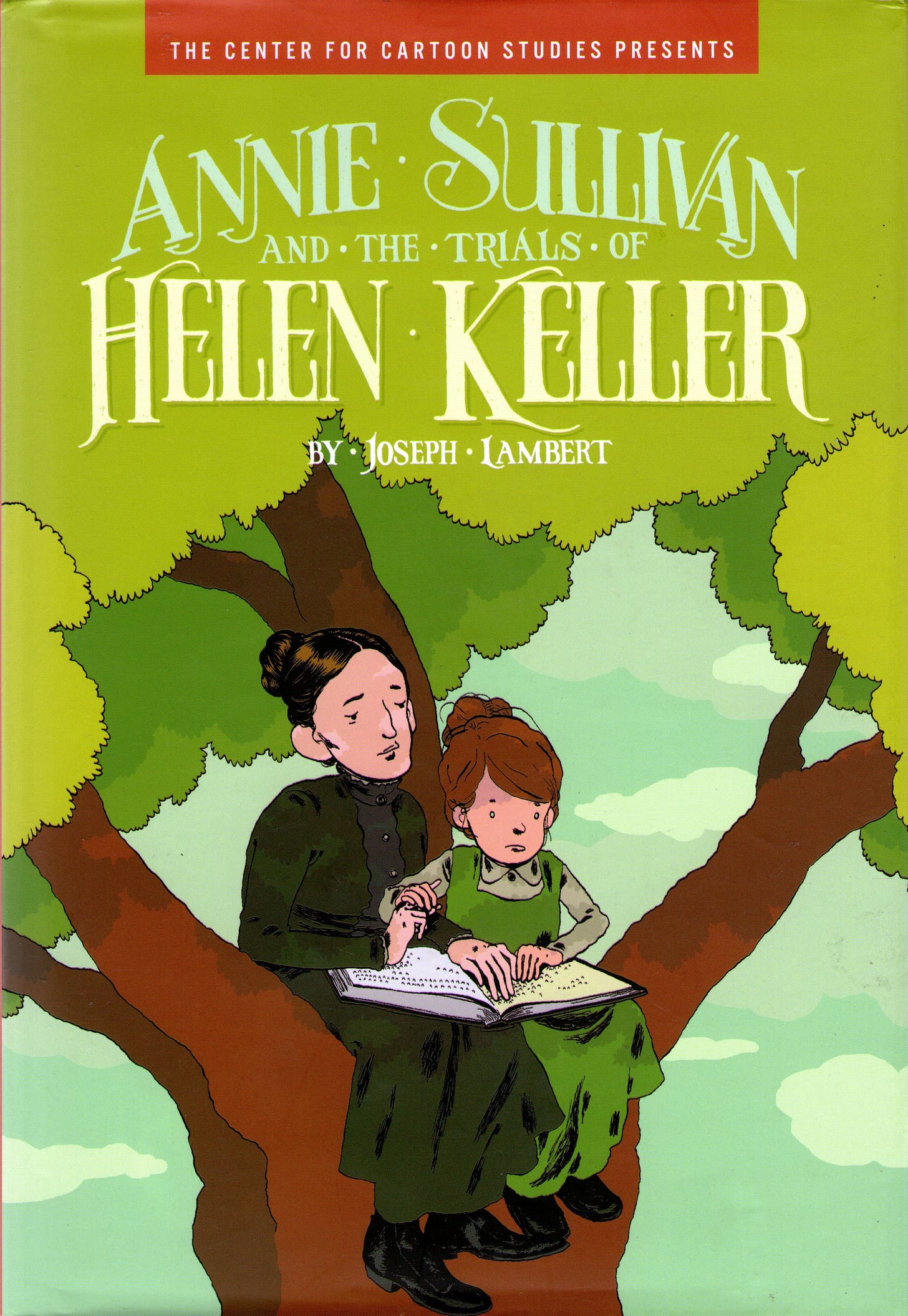

Required Reading is DoomRocket's love chest, opened once a month to champion a book that we adore and you should read. The latest: Joseph Lambert’s Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller, available now from Little, Brown and Company.

Joseph Lambert wants to draw you a map. The distance from here to there, how this turns into that because of what's between. Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller explores the journey of cognition, the mechanics of how we think, through the medium of comics. A visual interpretation of how concepts are perceived in a strictly proximal world, picturing life without sight or sound. Imagery that's more like infographics than sequential art is one side of the story, Helen's. The other side is how she met Annie, her teacher, and the despicable things society put the two of them through. Not the whole story — better than that.

Keller became blind and deaf in her infancy, before Lambert's story begins. The panels set from her perspective are about sensory perception. As Sullivan educated Keller, object permanence becomes grasping ideas: images and words mix together homogeneously. Once she learns the concept of naming things, Keller's surroundings transform into Dictionopolis. Images and words also share space without coming together, such as dialog (via word balloons) for those who speak and (to begin) images of hands spelling letters in sign language for those who don't. Lambert uses our familiarity with the parts of comics to take the reader through the development of both vocabulary and critical thinking.

Hand-spelling is a form of communication representative of the written and spoken alphabet. Keller and Sullivan speak in signs, and Sullivan provides — aloud — translation into English. W-A-T-E-R. P-I-T-C-H-E-R. P-U-M-P. From the repetition of association comes a recognition of identity, a name and a concept of permanent existence separate from the self. The hand-spelling turns into text as the nature of thought changes, and how we describe our world is shaped by it. Lambert's art is an inverted case of shadows on a cave wall, conceptual constructions are solid silhouettes of pure color emerging from total blackness.

Our proximal senses — touch, taste, smell — are how we interact with the world. Our distal senses — sight and hearing — are our perception of the world. Picture Helen Keller feeling something like warmth on her skin, not knowing the sun was shining on her. Lambert goes on to explore how we think about how we think. Keller has to trust that the world outside matches the picture of it she creates in her mind, but so do the rest of us. We call the light we see reflected down in the water the moon because we've never known to look up.

The bookends to Keller's Trials are discovery and doubt. Her development's unorthodox course and boundary-annihilating teacher lead to her persecution by strangers for political gain. Are her thoughts, comprised of what others have taught her, actually her own? The crisis Keller faced for writing fiction, where thought comes from and who owns it, has plagued humanity's great thinkers since the dawn of the written word. There's a perfect version out there, but what we know is an internal interpretation. Keller's absent distal senses meant that her perception of the sources of what she encountered was entirely secondhand. We see it in Lambert's art: the idea comes from the word, spelled out as a string of symbols through clasped hands, the story connecting the word to the hand is a speech balloon inside Keller's head, explaining.

But treating our perspective so austerely is to devalue imagination. We can picture things that have no perfect version. If thoughts need a real correspondent, is the thought of a unicorn a real thought? Not a lot of quantum psychology comics out there (there is K Wroten's Eden II)! Nobody told Helen — at least, not during the time she appears in this comic — that the infographic in her mind of tree and branch and leaf was closer to perfect than any physical expression out in the world could be. Life is gnarled, made of predictable patterns like long summer days and very small puppies, yet each leaf sprouts unpredictably.

I was tempted to look at the page layouts like a map (thanks to an essay on Bil Keane's dotted line by Michelle Ann Abate). Lambert uses a pattern of reserving space for communication that keeps the form static while modulating the content, different approaches rendered thematically consistent. The correspondence written by Sullivan and Keller (in their distinct handwriting style) or a string of hand signs spelling out a word occupies the same territory as speech balloons. Looking at the page cartographically reveals a clear division within the rows of panels, an invisible line between top and bottom.

Which makes sense; a speech bubble is up in the air because sound travels across space, projected from the body, from one body to another. In Annie Sullivan, it is a subtitle space, translating communication that originates in the body. Helen's communication is in the hand. Speech is the lungs and the throat, the shape of the mouth as breath is pushed out. The ideas that we write down come from the mind (and hand, like Helen).

Since words are such a pivotal character in Helen Keller's development, the methods of lettering Lambert employs ask for extra scrutiny. Slam, stomp, snip sound effects that self-describe are hand-lettered, placed in a way that mirrors how a verb like "sweep" is pictured in Helen's mind in relation to the image of the broom. The "slam" comes out of the door, not up in the communication zone, down covering the doorknob. The source of its voice is where Annie touched the door, blocking out the rest of the house. The noise of distinction in Annie Sullivan that doesn't have a meaning is the clattering sound the beds make in the poorhouse when they wheel out the dead. The experimentation with text is constant, not just for Helen.

Annie Sullivan excels at striking down the notion of the reader being taken out of the moment when craft interrupts the story. The dynamics of perception switch back and forth between Keller and Sullivan to show the learning process itself; their difference highlights their similarity. Lambert's style resembles a slightly sketchier Jordan Crane or Hartley Lin, or a mightily tighter Adam de Souza or Kevin Huizenga. That spare, indie cartoonist's ability to capture detail in an aloof, semi-scribbled way that allows for realism without photorealist standards. The proximal phantom world of Keller has less distance to bridge the distal one Sullivan perceives. Cartographic blocking seems contrary to the "potential" of comics, to resign the infinite offerings of imagination to drawing talking heads, but even outside the devices Lambert uses to explore visualizing cognition, the negative space that silence takes up in typical conversation gives something to the story's mood — power to its dialog — that would be lost in dynamic cinematography.

Thankfully, the cartoon mechanics of Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller are in service to documenting a critical part in Keller's life, not to diagram how a mind "overcomes" disability (or, more accurately, how a mind accommodates to fitting into the function of a rigid, exclusive society). Annie Sullivan honors Helen Keller. That said, Keller is a supporting character in Sullivan's story. We are privy to Keller's perception of the world but in the aforementioned style of inverted cave infographics, which are out of place within the general framework of the narrative. The comic is Sullivan's experience, her reflection and analysis, her past we flash back to for context of the world they live in, how it treats people like them. Annie Sullivan was an altogether extraordinary woman, a once-in-a-lifetime teacher from whom we all get to learn.

The nonlinear storytelling is more mapping, more of the reader following Lambert's routes. Visually, we travel through Helen's mind, connecting her sensory perception of things to her cognitive conception of ideas. Structurally, we travel through Annie's mind. Her struggles with Keller send us back to Sullivan's traumatic childhood, the school that turned her life around, and the drama of bringing real experience to educational circles, which led to her being the long shot to help Keller. It feels natural; a triggered memory retells itself, but really, the reader is unstuck in time like Billy Pilgrim.

Through Sullivan's story, we get a critique of how things are run. How we teach. In a traditional sense, there's Sullivan's discovery that, with accommodations, Keller developed as fast as the instruction could come. However, Sullivan also discovered a method of education in response to the pupil's interest and the substantive progress that can be made with student engagement. How we treat women. What Sullivan went through the educators in her peer group could hardly conceive of, let alone navigate. Yet Sullivan is socially powerless and achingly conscious of it. Her lack of compromise gave Keller words. How we treat the poor. Knowing Sullivan's story describes who she is with a fullness that a word like "teacher" doesn't cover. That which she experienced inspired the person she turned herself into.

Who moves the world? Annie Sullivan was no one. What she achieved was incredible, but the fate of a good person in this uncertain world of ours is to struggle. Focusing on the trials Keller underwent is an interesting approach for a graphic novel about the triumph of education. Williams and Keller's lives continue after the book ends, though I don't think the conflicted feelings the story left me with could be resolved by more stuff happening. It's there if that's what closure means to you. But the degree to which Helen's question is answered by Annie's experience is up to the reader to reconcile.

Did Keller ever learn that the creative process is a dismissal of self? The writer disappears as the writing reveals itself. She was alive at the same time as Roland Barthes. She died the year after his La mort de l'auteur was published, and she understood French. After her trial, she never wrote fiction again.

Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller is available now. For ordering info, click this.

Little, Brown and Company / $12.99

Written and illustrated by Joseph Lambert.

Edited by Jason Lutes and James Sturm.