A top-shelf blend of influences makes magic in Cat Mask Boy

Linus Liu's graphic novel shows how kids get along in an imperfect world.

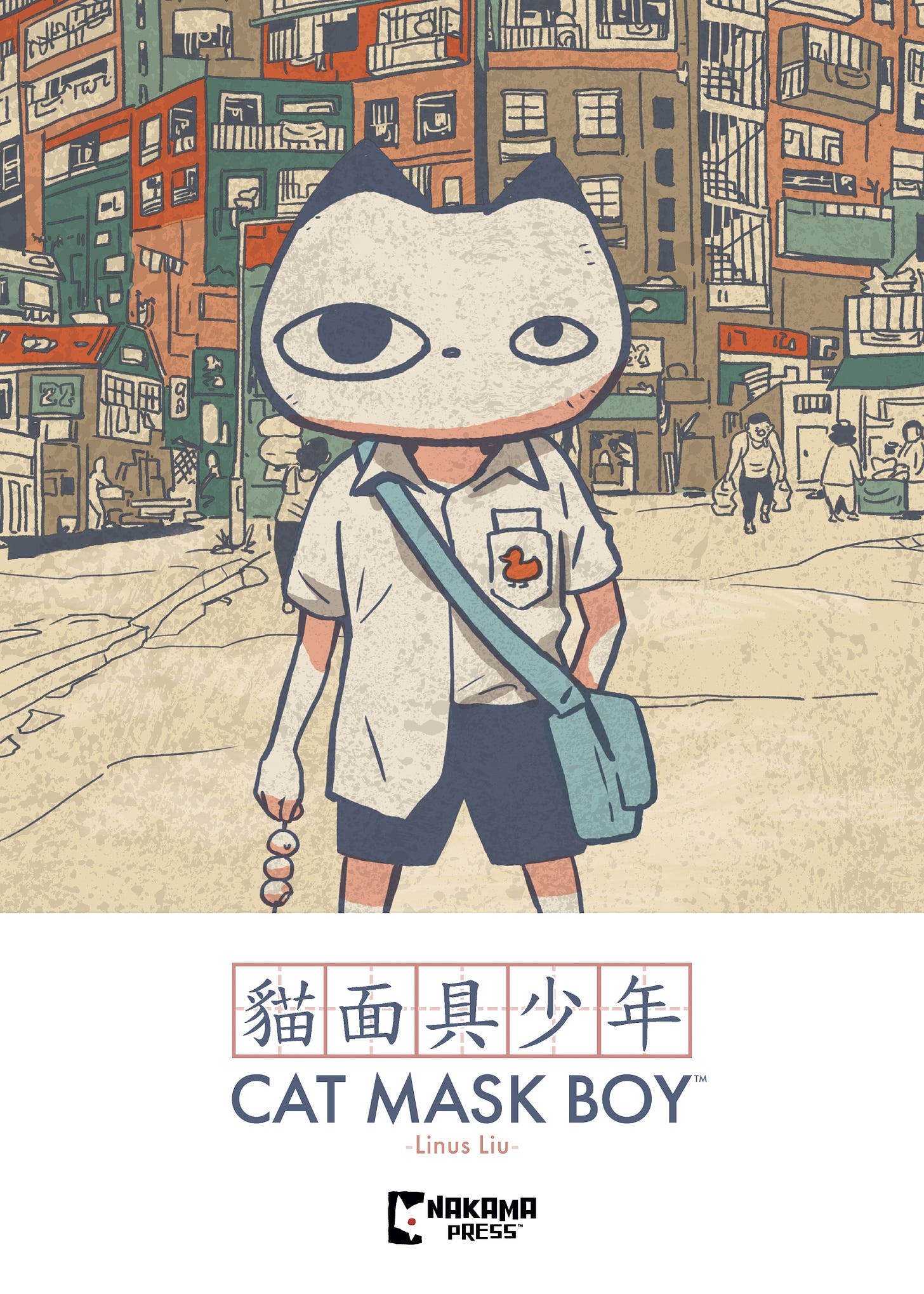

Required Reading is DoomRocket’s love chest, opened once a month to champion a book that we adore and you should read. The latest: Linus Liu's Cat Mask Boy, available now from Nakama Books and Mad Cave Studios.

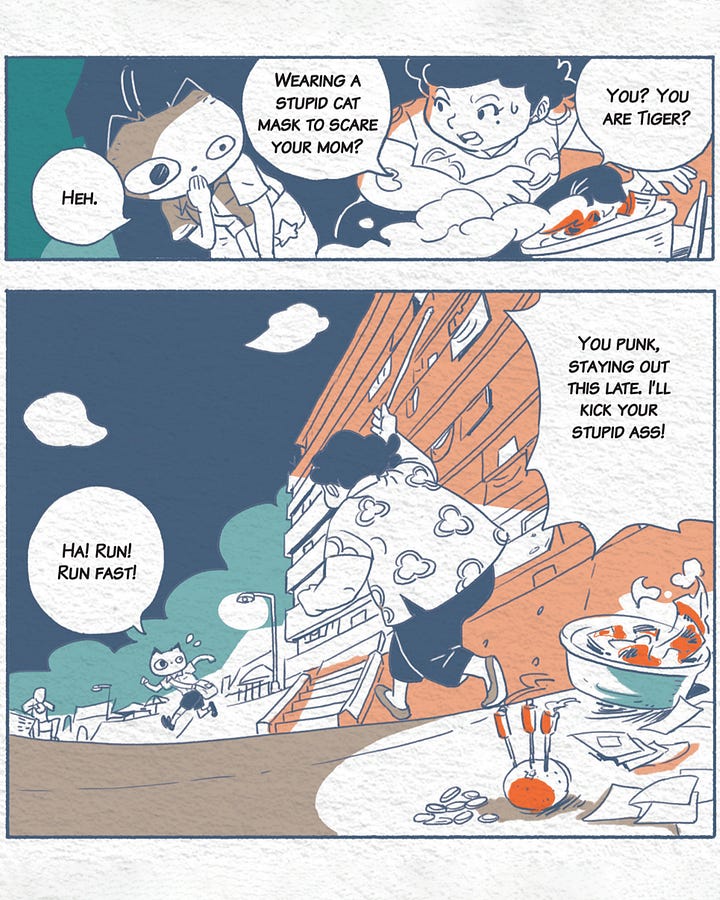

In the Kowloon Walled City, get lost and you might never come out again. You’d think that the hero in a book called Cat Mask Boy would be the one to fix your situation, but Tiger, Linus Liu’s kid with more moxie than muscle, is the one in trouble. Despite the mask he wears and his penchant for striking a Kamen Rider battle stance, Cat Mask Boy is about a boy with a cat mask, not a superhero. Not yet, at least. So not only has he taken the bus from his neighborhood into one of the dicier corners of Hong Kong in the 1970s, Tiger’s done it because he needed to find his lost report card.

The search to reunite a struggling student with his all-important misplaced paperwork, leading to an adventure in an unknown part of town, reminds me instantly of Abbas Kiarostami’s film Where Is the Friend’s House? Both give a weight to the trivial that feels true to childhood’s innocent perspective. There’s maybe some Lynne Ramsay Ratcatcher in there, as well, in the way the games and play persist despite the poverty, how innocence is lost and innocence endures. A fantastic yet realistic take that shows how kids get along in an imperfect world.

You know it’s fiction from a kid’s point of view because the adults actually treat them as if they are important. Tiger gets chastised for being impractical — an inescapable aspect of childhood — but his impossible inclinations are entertained. The paper lantern-esque prosthetic cat head he wears to class is acceptable, but he should know that being a superhero is not a valid career path for a young man’s future.

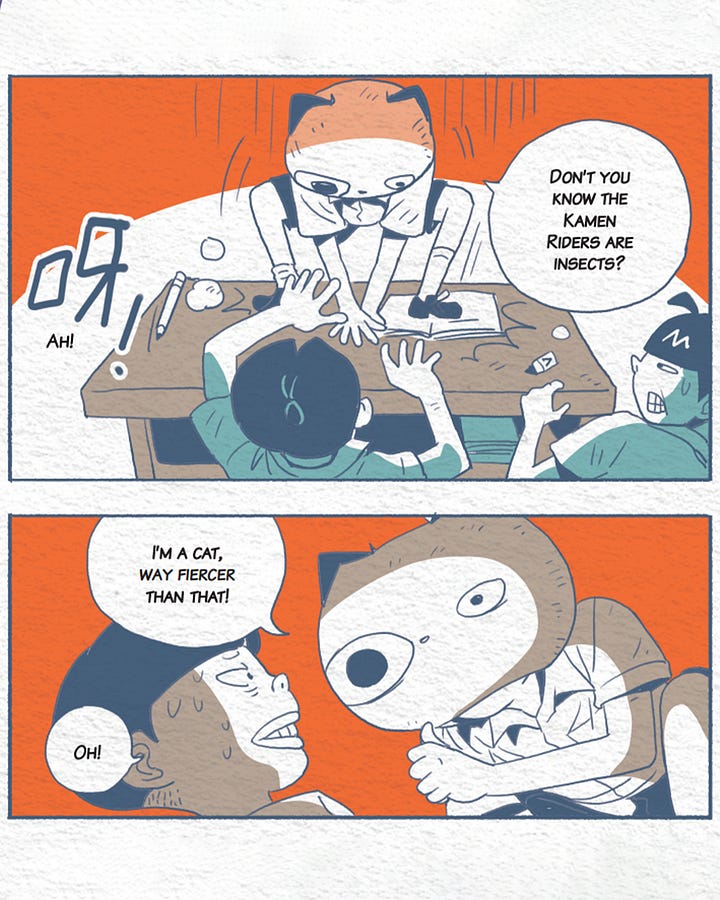

Dragon, the cat mask boy of the Walled City, has got to be my favorite character. Maybe because I find him relatable? When I was that age, I would scrap in the schoolyard with kids who bullied other kids younger and smaller than them. Dragon lives a life more like Snufkin than I did, if Snufkin watched a lot of Kamen Rider. Kid, yes, and the wandering warrior who shows up late in the wuxia. And I love that he’s a big kid. While some of that is playing to a gentle giant archetype, he’s definitely rounded, not ripped. It’s refreshing to see the fitter of the two heroes (harder, better, faster, stronger), in a comic book no less, is the one built like Igaguri or Kube.

The Rider worship — one of a couple of Crayon Shin-Chan parallels — is nice. Not only because the book delivers the occasional two-foot dropkick, but there’s something that works with the age and innocence of the three cat mask kids. Tiger’s naive imitation of Kamen Rider morality is actually put to the test when he crosses town. The hero action gets legit in the presence of real danger, meeting the story’s rising tension, as night falls and still no report card.

There’s a side-quest that Dragon and Tiger complete on their way from the dentist back to the bus route. The two cheating kids, and their game of pogs before pogs were a thing, playing with their trading cards like marbles: keep what you knock out of the ring. Dragon returning the character cards he won to the kids (rapscallions straight out of a Zao Dao comic) after he wins the game is such a cool dude move. They gotta have cards if he’s gonna beat ‘em again tomorrow, right? Love that.

But also the cards themselves — more Rider worship. Icons are important to kids, and Cat Mask Boy shows the reader how kids express that, how they act, what they do, rather than Liu telling his readers what kids think. It resonated with me, not because I have childhood nostalgia for a specific tokusatsu franchise, but because I had fictional people I unreasonably wanted to be, and when I could, collected ephemera with their images on it.

There’s a little bit of Gilbert Hernandez’s Palomar (from Love and Rockets) in there as well, the early stories when they were still kids. The guy who ends up with the report card for a while — because by chance he stopped at the shop run by (the third cat mask boy) Rocky’s mother when the cat mask boys were hanging out — he’s a Beto dude. He goes to the Walled City to get cheap, good work done by the hot dentist who smokes in her office. Tracking her down leads Tiger to the side of town where kids need a local chaperone like Dragon. Different backgrounds, different lives, sharing the same little spit of city, crossing paths without knowing how connected they are. You never know who you are going to bump into.

Liu’s work keeps finding comparison in my mind to art made for adults about kids, rather than art made for kids, despite Cat Mask Boy ostensibly being an all-ages book suitable for young readers of Tiger, Dragon, and Rocky’s age. It certainly defies as many kid lit standards as it fulfills. Cat Mask Boy shows you Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences, overtly through streetwise Dragon, covertly through Tiger’s wheeling and dealing, so that he has the time to pursue a craft that makes him happy without letting his already bad grades slip any further. But what Dragon says out loud is school sucks. Education can only take you so far. Personal growth doesn’t come from study; it comes from practice.

Between that, the parents whipping their kids’ asses for disobedience, smoking doctor, body humor at the urinal trough, I mean, good luck getting it into a school library in the 2020s. To their credit, librarians are the ones who see past what’s deemed problematic by the consensus and recognize the value in books like Cat Mask Boy. It’s the public’s penchant for easy categorization that this one defies.

Cat Mask Boy doesn’t readily fit in with the established ways we put comics together. From a cultural association and marketing standpoint, it is a YA OGN with a limited palette indie aesthetic about coming of age outside the global North. Its publisher, Nakama Press, addresses the manga market’s contemporary expansion into other suffixes, in this case, as manhua. Nakama is, of course, a manga imprint of Mad Cave, an indie comics publisher out of Miami.

So an indie comics creator from Hong Kong, like Liu, fits in perfectly. And to the story’s point, school can teach you some things, but pretending it’s the beginning and the end of education is only going to hold you back. Liu tells the stories of the kids who are seeds. You know, the buried ones, the flowers that bloom by coming up through cracks in the cement.

Cat Mask Boy is told from that place of compression and growth instead of about it. Dragon isn’t some roughneck monk filled with wisdom only available on the other side of the wall (both proverbial and literal in this setting). He’s just a little older. If anything, someone like Dragon, who lives “outside” traditional society, is actually living a fuller realization of what society is than a Tiger does.

I think Liu’s inseparable blend of moods, influences, and goals comes up with some real magic. Each Cat Mask Boy episode’s title card/chapter heading gets its own splash page, and the climax with the gangster chasing the kids up the tenement stairs is way more like Matheiu Kassovitz’s La Haine than a YA OGN has any right to be. The kids are a half-flight ahead of the enraged adult’s bruised ego, slashed face, and clenched fists. Dragon is already disappearing between art deco railings and exposed ceiling wires on the next floor’s landing; Tiger’s head is down, shirt flapping behind him half-untucked as he closes in on the top of the stairs.

The filmic framing and body language of the characters scream David Mazzucchelli wrapping up Year One, while the colors and the wispy, wobbled, hand-wrought quality of the lines strongly recall Jordan Crane. There’s another influence that’s harder for me to put my finger on, something in how Dragon’s physique curves, how men’s faces have a big shape in the middle for a nose, that communicates retro manga to me, but as a general aesthetic and not a specific artist. Mitsuteru Yokoyama and Shotaro Ishinomori, stepping out of the past, but still of it.

This is just one page; this is what I mean by magic.

Cat Mask Boy is available now. For ordering info, click this.

Nakama Press / Mad Cave Studios / $10.99

Written and illustrated by Linus Liu.

Translated and lettered by Book Buddy Media.

Production by Camilo Sánchez.

Edited by Kristen Simon.